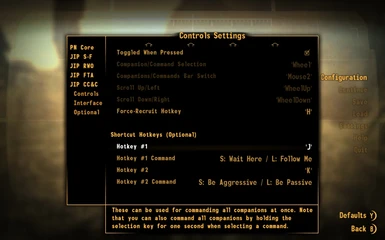

Jip Companions Command And Control Not Working

- Manual Command Conquer Tiberian Sun Walkthrough For Pc Requirements. Also be read in the JIP Companions Command and Control, a copy of the complete walkthrough in the items disappears, activate the computer rack between the mainframe and the There are. Manual Command Conquer Tiberian Sun Walkthrough For Pc Requirements Created Date.

- Also I don't care if it's not lore friendly. I have played this game so many. JIP Companions Command and Control Light Up And Smoke Those.

New animal companions. Improved Companion Sandbox. Allows companions to do things while you set them to wait. JIP Companions Command and Control. Gives increased control over followers. RobCo Certified. Robot companions and lots more. Unlimited Companions. Allows you to have an unlimited amount of companions at one time.

Command and Control. In the military, the term command and control (C2) means a process (not the systems, as often thought) that commanders, including command organizations, use to plan, direct, coordinate, and control their own and friendly forces and assets to ensure mission accomplishment. Command and control of U.S. armed forces today is the result of a long historical evolution. From 1775 to 1947, there was no common superior to the War and Navy Departments and their respective military services, except for the president of the United States, who was commander in chief of the army and navy under the Constitution. Only in 1947 were all the military departments and services unified in principle.

The rudiments of U.S. national military command and control emerged in 1775, when the American colonists challenged the government in London and ultimately obtained independence from the mother country. Initially, the American colonists were loosely organized and lacked a recognized military commander. The Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia and on 15 June 1775 named Gen. George Washington commander in chief “of all the continental forces raised, or to be raised, for the defense of American liberty.”

After 1776, the Continental Congress acted as the principal coordinator of the war effort of the American colonies. It organized an army and navy and appointed commanders of these forces. However, there was no clear direction as to whether Congress or the commander in chief was to devise strategy. Unwilling to put a single person in charge of the war effort, Congress appointed a committee, the Board of War and Ordnance, in June 1776. But the board did not work satisfactorily, and Congress kept close watch on the military and its commanders. The war proved the need for strong, central direction and the subordination of state to national interests.

The new Constitution of 1789 created a separate executive branch, but declaring war, raising armies, and providing for a navy was assigned exclusively to Congress. In March 1789, Washington became the first president under this Constitution, and as such he was also designated commander in chief of the army and navy. The Department of War was established on 7 August 1789; the secretary of war headed the War Department and was a deputy to the president in military matters. The Navy Department was not created until 30 April 1798.

In the War of 1812, the lack of a senior line officer in the chain of command to act as adviser to the secretary of war and the president proved a serious deficiency. Command and control of the U.S. Army and Navy remained essentially unchanged between 1821 and the beginning of the Civil War in 1861. The president was commander in chief of the army and navy, while his two civilian deputies ran the War Department and the Navy Department. In command of army troops after 1821 was the senior army officer, the commanding general or general in chief. However, his duties were left undefined. There was no corresponding position for the navy.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the Commanding general of the army was made responsible for the efficiency, discipline, and conduct of the troops, while the secretary of war was responsible for the administrative and technical services. The latter also controlled budget, and all the army bureau chiefs reported to him. The secretary of war was a civilian, often with very little military experience, and he depended for guidance on bureau chiefs. Hence, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant proposed in 1866 to place the Adjutant General under the control of the commanding general of the army, who was to be responsible directly to the president through the secretary of the army in all army matters. No action was taken until 1869, when General Grant became the president and issued an order putting his proposal into effect.

The Spanish‐American War exemplified all the worst features of the archaic U.S. system of military command and control. The lack of military planning and very poor coordination between the services led to general confusion and inefficiency. Nonetheless, the war was successful, due to the initiative, courage, and endurance of the American soldier and his immediate superiors.

The underlying cause of friction and confusion in the War Department was between the commanding general of the army and the bureau chiefs. The new secretary of war, Elihu Root, proposed to abolish the position of commanding general, and the new position of chief of staff of the army was created. That officer was to be in charge of all army forces and the staff departments, and directly responsible to the secretary of war. The chief of staff would act as adviser and executive agent of the president through the secretary of war. Congress adopted Root's proposal in February 1903. Another significant change proposed by Root and approved by Congress was the creation of a General Staff Corps (patterned after the Prussian system but greatly reduced) of forty‐four officers to prepare plans for the national defense and for the mobilization of the military forces.

The disruptive experiences of attempted navy‐army cooperation during the Spanish‐American War led to an attempt in 1903 to improve matters by institutionalizing coordination between the two services through a Joint Army and Navy Board, consisting of four army and four Navy officers. However, the Joint Board did not have a group of officers to do the planning. Its work was suspended by President Woodrow Wilson in 1914, and it did not play any role during World War I.

National command and control underwent some changes in the 1920s. The National Defense Act of June 1920 remained the principal piece of legislation pertaining to the U.S. Army until 1950. The Joint Board was reestablished in 1919 and its membership increased to six. In contrast to its predecessor, the newly reestablished board acted continuously. It was also provided for the first time with a subordinate staff group: the Joint Planning Committee.

In 1922, the Joint Committee on the Reorganization of Government Departments proposed that the army and navy be unified into a Department of Defense under a single cabinet secretary, who would be assisted by undersecretaries for the army, the navy, and for national resources. Nothing came of these efforts because the two military departments opposed unification. A further attempt by Congress at unification failed in April 1932.

In 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt placed the Joint Board, the Joint Economy Board, the Aeronautical Board, and the Army‐Navy Munitions Board under his own direction as commander in chief. The Joint Board of the Army and Navy was never organized as a body to provide strategic direction; its meetings were held only once a month, while its Joint Planning Committee met twice a month. A more serious problem was that any decision of the Joint Board required the approval of the secretaries of war and the navy before it could be effected. By May 1941, the Joint Board established a Joint Strategical Committee as a part of the existing planning committee. Its major responsibility was to draft joint war plans. In July, the Joint Board began to meet weekly.

The Joint Board evolved into the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) as a result of a visit by British prime ministerWinston S. Churchill and his military advisers who came to Washington in late December 1941 to confer with President Roosevelt about collaboration in the war against the Axis powers. By early 1942, a decision was made that the Combined Chiefs of Staffs (CCS)—a collective term for the U.S. and the British chiefs of staff—were to pro‐vide strategic direction for all operations under Anglo‐American responsibility. The first formal meeting of the CCS took place on 23 January 1942.

The chiefs of staff of the various U.S. armed services held their first meeting on 9 February 1942. Afterward, the chiefs of staffs constituted themselves with tacit approval of the president as Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Joint Board for all practical purposes ceased to operate. Initially, the JCS served as the U.S. representative of the CCS and as the coordinating agency for the war efforts of the army and navy, directly responsible to the president. The JCS was also in the direct chain of command of each U.S. theater commander. No legislative or executive action was taken to formalize the JCS until the National Security Act (NSA) of 1947 was adopted. This proved to be an advantage, because it allowed a great deal of flexibility and innovation in the work. The act created the National Military Establishment (NME) and the civilian secretary. It unified all the services and created co‐equal cabinet‐level secretaries for the new Departments of the Army, Navy, and Air Force. The roles and missions of the military services were specified in an executive order (Congress did not do the same until 1958). The NSA also legalized both the JCS and its Joint Staff. For the first time it defined the term combatant command. The “unified” combatant command was defined as a command composed of forces from more than a single military department and with one broad, continuing mission.

The act became effective when Secretary of Defense James V. Forrestal took the oath of office on 18 December 1948. The act also established the National Security Council (NSC) as the principal forum to consider national security issues that require presidential decision. NSA was subsequently supplemented or amended by several other pieces of legislation and executive agreement. The Key West Agreement of 1948 clarified the residual roles left to the military departments. It also allowed members of the JCS to serve as executive agents for unified commands—a responsibility that enabled them to originate a direct communication with the combatant command. (This authority was canceled by a 1953 amendment to NSA.)

The NSA was amended in 1949 and the name of the NME changed to Department of Defense (DoD). The secretary of defense's position was strengthened by his appointment as the head of an executive department. The authority of military department heads was reduced, and they assumed budgeting responsibilities. In 1953, the president and secretary of defense agreed to designate military departments to function as “executive agents” for the unified commands. Also, the chairman of the JCS was not to exercise any command over theater forces. The Reorganization Act of 1958 further clarified the direction, authority, and control of the secretary of defense; moreover, the act clarified the operational chain of command by stipulating that it ran from the president and the secretary of defense to the combatant forces, thereby removing military departments from the operational chain of command and redefining their support and administrative responsibilities.

The most important piece of legislation on national defense since 1947 was the Goldwater‐Nichols Act of 1986. It was specifically aimed to enhance cohesion between the services, clarify the chain of command, and further strengthen civilian control over the U.S. military. It also strengthened the position and authority of the CJCS. The chairman became principal military adviser to the president, secretary of defense, and NSC. However, in presenting his advice, the CJCS was required to present the range of advice and opinions he had received, along with any individual comments of the other JCS members.

The 1986 act also created a new position, vice chairman of the JCS, and two new directors of the Joint Staff. The size of the Joint Staff was expanded but limited to 1,627 personnel. The vice chairman is the second‐ranking member of the armed forces and replaces the CJCS in his absence. The National Defense Authorization Act (1993) vested the vice chairman as a full voting member of the JCS.

In legal terms, the National Command Authorities (NCA)—that is, the president and the secretary of defense or their duly deputized alternates or successors—retain ultimate authority and responsibility for U.S. national security. The DoD Reorganization Act (1986) reiterated that the chain of command runs from the president to the secretary, and from the latter to the combatant commanders. A provision permits the president to authorize communications through the CJCS. Presidential directive 5100.1 of 25 September 1987 placed the CJCS in the communications chain of command. Communications between the National Command Authorities and the combatant command pass through the CJCS. Directly subordinate to the NCA in the operational chain of command are five geographical combatant commands (Atlantic, Central, European, Pacific, and Southern) and three functional combatant commands (Strategic, Space, and Transportation).

U.S. national military command control today is much more effective than it was only a decade ago. Civilian control of the military is preserved and strengthened. The operational chain of command is simple and clear. And the geographic combatant commanders possess the necessary resources and authority to accomplish their assigned missions.

[See also Civil‐Military Relations: Civilian Control of the Military; Commander in Chief, President as.]

Bibliography

Jip Companions Command And Control Not Working Windows 7

Louis Smith , American Democracy and Military Power: A Study of Civil Control of the Military Power in the United States, 1951.

Maurice Matloff, ed., American Military History, 1956.

Harry T. Williams , Americans at War: The Development of the American Military System, 1956.

Samuel P. Huntington , The Soldier and the State: The Theory and the Politics of Civil Military Relations, 1957.

Demetrios Caraley , The Politics of Military Unification. A Study of Conflict and the Policy Process, 1966.

Edward Kolodziej , The Uncommon Defense and Congress 1945–1963, 1966.

C. W. Borkland , The Department of Defense, 1968.

Russell F. Weigley , The American Way of War. A History of United States Military Policy and Strategy, 1973.

Mark D. Mandeles, Thomas C. Hone, and and Sanford S. Terry , Managing “Command and Control” in the Persian Gulf War, 1996.

How to uninstall protools. Do you fail to install the updated version or other program after uninstalling Pro Tools LE 6.4? Many computer users can not completely uninstall the program for one reason or another. Do you receive strange errors when uninstalling Pro Tools LE 6.4? If some files and components of the program are still left in the system, that means the program is not completely removed and uninstalled.

Milan Vego